When a young boy from Alexandra told his mother he had a secret in January of 1880 he was to reveal a shocking situation which he and his friends had found themselves in. The afternoon before had begun well enough – a summer’s day and over 10 boys gathered at the Mangapiko Creek. When one of them suggested they should get in the water, they all, except Claude Aubin, 7, undressed and got in. None of the boys could swim.

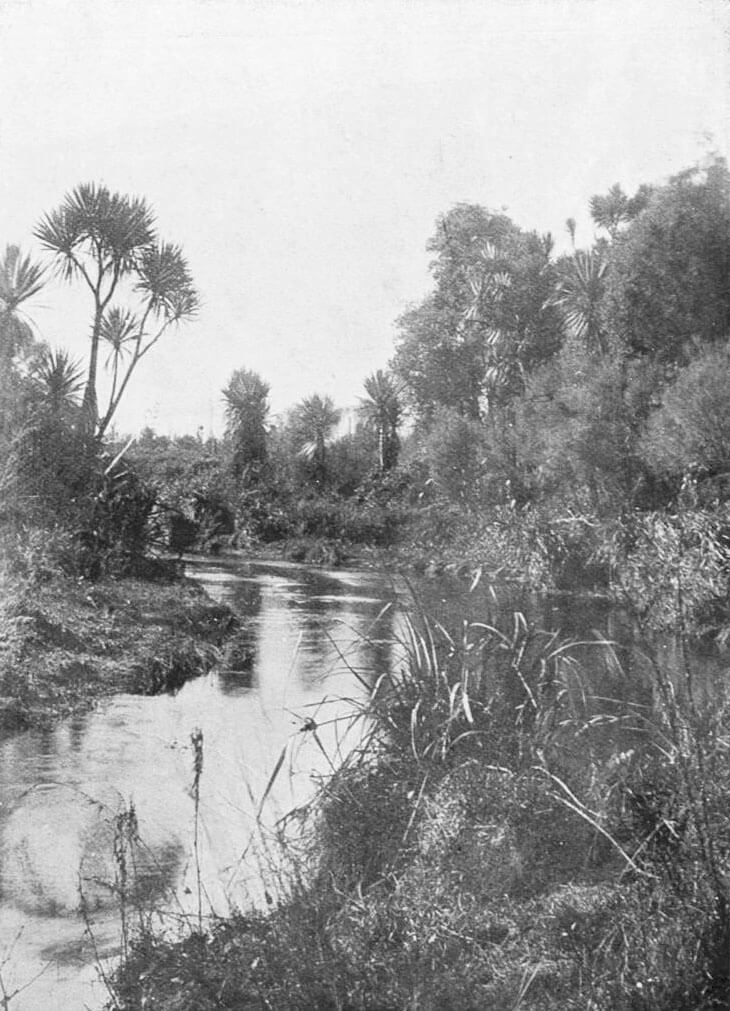

A bend in the Mangapiko Stream, Te Awamutu

Ted Sage, 13, took Albert Bayliss and Edmund Sturmer, both 9, by the hand and ferried them over to the other side of the river. After playing for some time on the sandbank Ted told the boys it was time to go back. Somehow in getting back across Edmund and Albert got away from Ted, who, just as he was getting out of the river he heard the other boys calling out, “They are going down; they will be drowned.”

Ted called out to them to try and catch Albert and Edmund. He ran down the side of the river, but could not see either boy for a minute or so. Then he saw Edmund’s head come up out of the water two or three times, before Edmund caught hold of a tree branch. Ted jumped down the bank and caught him by the wrist and pulled him ashore. Ted could not see Albert anywhere. He and Edmund went back to the other boys who asked where Albert was, but no one had seen him.

Unsure what to do, the frightened boys dressed and in their anguish made a terrible decision. Someone asked, “What shall we do with his clothes?” Ted said: “Leave them lay somewhere about here,” and Herbert Hutton also said, “Leave them lay here.” Willie Pierce, 10, took the clothes and went out of sight across a small creek and put them in the fern. The boys agreed to say nothing to anyone. They all left wondering if Albert was drowned. Ted reached home about 5pm and saw his sister. He said nothing to her, or to his father, who he saw shortly afterwards. Ted was frightened of getting a beating from his father, who had told him to come home straight from school.

The next morning one of the boys told his mother the secret and she at once informed Albert’s father, John, who, along with his wife Harriet, must have been beside themselves at the mystery disappearance of their son. John Bayliss went to the Sage’s house and asked Ted where Albert was. Ted at first said he did not know, but soon confessed. Constable McLeod, along with Albert’s father, Mr Pierce and Constable Moule began searching the river. Around 8am Albert’s body was found caught in a snag.

Albert was John and Harriet’s second son. He, his parents and four siblings had come to New Zealand as assisted immigrants on the ship James Wishart in 1874. Their journey to their new life was made memorable by the eccentric ship’s Captain Groundwater who was described as being at home when at sea and at sea when in port. When a reporter, as was usual on the arrival of an immigrant ship, asked for details of the voyage the request was refused by the Captain in the surliest of tones. “Under the circumstances we give a somewhat curtailed report of the passage,” he had to record. Among the 278 immigrants were a wheelwright, a sugar-baker, a harness maker, bricklayers, blacksmiths, domestic servants, and labourers of which John was one. The Baylisses had two more children and settled at Alexandra, where John was now employed managing Dr Waddington’s farm.

At the inquest into Albert’s death the boys’ evidence was conflicting. The Coroner focused on the discrepancies, but considered that although the boys were much to blame for concealing the occurrence, they no doubt had been greatly frightened by the suddenness of the accident, and they were scarcely of an age to act with much discretion. There was no evidence whatever of any malice, and it was quite clear that they were all playing together when Albert accidentally drowned.

It is unclear where Albert was buried.