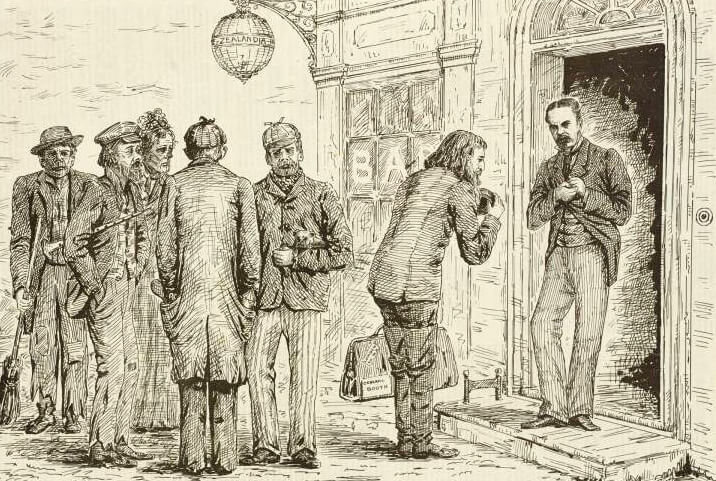

Ten years after Alexander’s death attitudes hadn’t really changed – John Ballance, Prime Minister, refuses to let the Salvation Army bring in ‘homeless vagrants’ to settle in the country.

When 80-year-old Alexander Kemble was staggering the streets of Alexandra in great agony in January 1881 there was a dilemma as to what should be done with him.

There were no police in the district and their equivalent, the Armed Constabulary, said they had no power to do anything in such a case. One of them, however, led Alexander to the hotel, and as a last resort Mr Finch took him in.

Alexander had been partially crippled by a falling tree at Howick some years previously. He was severely injured internally which incapacitated him from performing any laborious work. He had, however, managed to scratch out a precarious living recently by cutting firewood in Pirongia. Despite his infirmities he was a man of energy and independent spirit and had formerly belonged to Captain Peacock’s Company of the 2nd Regiment of the Waikato Militia.

But now Alexander was quite destitute, and when he had come into the settlement two days earlier, he was in terrible pain with no way of affording medical help.

There were big cracks in the poor relief system at the time and Alexander seemed to have had fallen through all of them. New Zealand’s government did not want the workhouses of Britain repeated in this country – these institutions were intended to provide shelter, sustenance and work to the poverty stricken, but life there was dreadful. The government consequently had scarcely any involvement with the needy and mostly left their care to relatives, friends or charitable institutions.

The homeless, the poor, the sick or those looking for work could be arrested as vagrants under laws classing them as idle, disorderly or wandering abroad. Vagrants were sent to jail, lunatic asylums or shelters. Often they were sent back repeatedly when their grim circumstances saw them re-arrested. There was not even a military pension for Alexander as he was injured following the New Zealand wars.

Despite New Zealand priding itself on having no workhouses, in 1880 institutions remarkably like them started to appear under more palatable names such as Old Men’s Refuges, set up in derelict buildings, old hospitals and immigration barracks. A great necessity existed for some kind of organised Government relief to assist destitute sufferers like Alexander.

But relief for Alexander came too late. Dr Blunden, of Te Awamutu, was sent for, and everything was done for him that could be but collapse set in and his recovery was impossible. His cause of his death was attributed to his old injury, inflammation having set in his intestines or bladder.

Alexander was a man of strict sobriety, who had a horror of being thought of as vagrant. He was never known to enter a public house until the desperation of his final days. His death scandalised the community who felt hotel proprietors were sufficiently handicapped with taxes without having their public houses turned into hospitals. Alexander was well thought of and his funeral attended by all the districts’ old settlers and many others acquainted with the stoic gentleman.