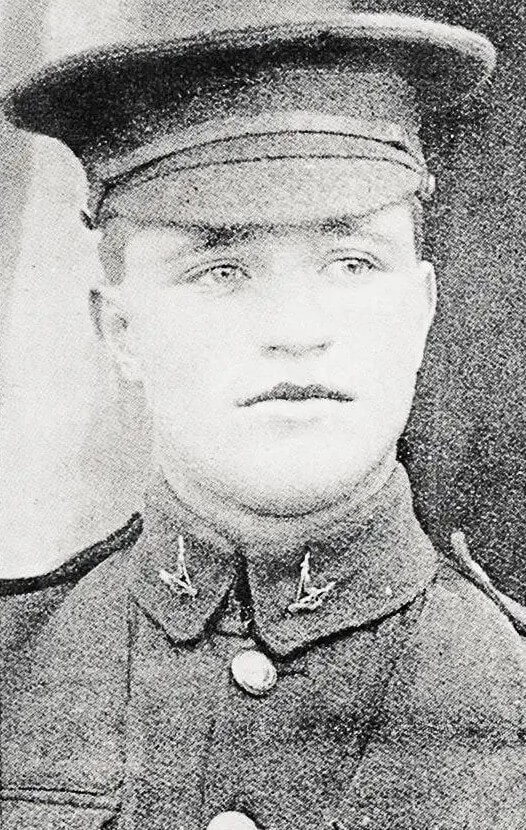

Private Carl Sittauer, 16th Waikato Company – died of wounds in action at the Dardanelles in 1915.

It was only a splinter of tawa wood but after five days the tetanus bacteria it introduced into 13-year-old Vincent Sittauer’s bloodstream took his life. It was December 1885 and New Zealand had not been quite what Vincent’s father, Josef, had anticipated.

Josef, his wife Margarethe and their two infant sons had emigrated from Bohemia in 1875 but within months of settling at Ōhaupō Margarethe had died aged 27. Most Bohemian settlers were small farmers granted sections of land, initially living in small whares, growing food crops and rearing pigs and chicken. Craftsmen, such as blacksmiths and shoemakers were among the Bohemians and Josef was a bootmaker.

He remarried in 1879 and he and his wife Helena would go on to have a large family. Josef soon proved himself a settler of the right stamp and was quick to help his community when, in 1890, winds blew a bushfire straight towards Ōhaupō village and set alight the roof of Mr Edwards’s store. Josef, later described as working like a Trojan, chopped a hole through the roof so bucket brigades could quench the flames.

In the hot February of 1902, 15-year-old Peter Sittauer was with a group of boys at Horseshoe Lake (Lake Waiwhakareke) – now part of Hamilton. They pushed a boat out several yards from the shore and Peter, who could only swim a little, paddled around it but was suddenly in difficulties. William Carr dived in to the rescue, but after a struggle he had to let go his hold as Peter was pulling him under. William showed great pluck, making two gallant rescue attempts. Peter’s body was recovered by Constable McPhee, who kept the dragging operations going till dusk. An inquest found that Peter was accidentally drowned while bathing. The jury, at the suggestion of the Coroner, sent a message of condolence through the foreman to the bereaved parents.

Two months later Josef poisoned his thumb and in yet another terrible blow the bootmaker had to have his hand amputated at Waikato Hospital. Great sympathy was felt for the Sittauer family in their troubles and donations to aid his family – a wife and eleven children – were collected. By August Josef was back at work – advertising his thanks for past favours and promising footwear ‘repairs neatly done and prices reasonable.’

When World War One broke out in 1914 Carl Sittauer, 21, who had been keenly interested in the territorial movement, was among the first to volunteer for service. When news reached Ōhaupō in 1915 that he had died from wounds received in action at the Dardanelles, his parents had the heartfelt sympathy of the whole community on yet another loss of a son.

Something went wrong for Martin Sittauer and in a way he was lost to the family too. He left a trail of petty crimes and false names and by his early 20s had disappeared, perhaps overseas, perhaps to live out a life under an assumed name.

Vincent and Peter were buried at Ōhaupō Catholic cemetery, and Carl at Beach cemetery, Turkey (Gallipoli).